Yesterday (21st October 2016) a mass Distributed Denial of Service (DDoS) attack was initiated against Dyn. “Who are Dyn?” you ask, Dyn is a DNS Name Server provider whose services are used by a lot of major companies and websites.

Some of Dyn’s major clients include:

- Netflix

- Github

- Spotify

- Amazon

- Phizer

- Trip Advisor

- T-Mobile

amongst others. During the attack, these services were either responding slowly or not at all.

Whilst this attack appeared to take a lot of popular websites down, and the media reported it as a major cyber attack against all these companies, what was misreported was the fact that none of these services was directly affected. For example, I was attempting to commit the code I’d been working on all day back to Github at the end of the working day, but was unable to do so. Reading that Dyn was under attack, I simply searched for Github’s IP address on Google and added it to my local machine’s hosts file to sidestep the DNS lookup of github.com and was able to quickly push my code up before leaving the office.

DNS, what it is and how does it work?

But, let’s go into a little bit more detail on what DNS is, and why an attack like this crippled the Internet for a few hours.

Every device on the public facing side of the Internet has an IP address, currently the majority of services use an IPv4 system which consists of four 8 bit segments (known as octets – oct meaning eight) separated by dots. These 8-bit segments are represented by decimal numbers between 0 and 255.

An example of an IP address would be: 198.51.100.54

This IP address is a non-existent address used for documentation purposes in accordance with the ITEF’s RFC 5737

Web browsing could be done by contacting the relevant service by its IP address by opening a web browser and typing something like http://198.51.100.54/index.htm into the address bar. Of course, remembering all these addresses for everyday browsing may not be easy for some people. Thankfully the Domain Name System, or DNS, exists which maps these IP addresses to text-based addresses which are a lot easier to remember.

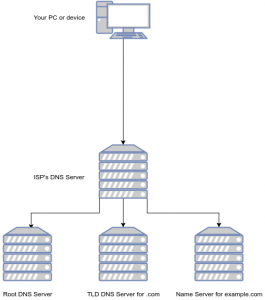

Think of DNS like a telephone directory, in which you request the number for a name you have. When you type the name of a website into your browser, such as http://example.com, your device will talk to a DNS server, usually provided by your Internet Service Provider (ISP), or a 3rd party such as Google DNS or OpenDNS if the user has set that up. If the site has been accessed recently, there’s a good chance the IP address of the service you’re looking for has been cached, and the website will load. But if this isn’t the case, the DNS service will pass your request on to one of the root DNS servers which passes you to the DNS server which handle the Top Level Domain name (TLD) such as .com or .net. The TLD’s name server will then be able to provide the Name Server records (NS Records) of the domain you’re looking for (such as example.com).

These Name Servers will then be able to provide the IP addresses of the domain, and subdomains of the service you’re attempting to access.

Back to the attack, what could be done to prevent it?

The attack on Dyn affected services that have Dyn’s Name Servers managing their domain. When a user requested a service whose IP address wasn’t cached, the DNS lookup would get as far as knowing Dyn’s name servers were supposed to be providing the IP address of the service to the user, but with Dyn under attack, the final part of the lookup would timeout. Some web browsers would mistakingly report the code NXDOMAIN which means the domain name is invalid (or doesn’t exist).

Unfortunately, not a lot could be done to avoid this attack, hitting a major part of the web’s infrastructure is obviously going to have a significant impact. There’s also a few companies misinforming potential customers that they were immune to the attack because their service was unaffected. (000webhost, I’m looking at you)

000webhost’s propaganda post on Facebook, misinforming users that they were totally immune to the attack.

Whilst 000webhost might not have been affected by this attack, they were simply lucky in that their service was using Cloudflare‘s DNS services rather than Dyn’s. Using their “propaganda” we can confirm this to be the case:

Let’s say we do a look-up of the NS servers for wix.com:

$ nslookup -type=ns wix.com

Server: 212.159.6.9

Address: 212.159.6.9#53

Non-authoritative answer:

wix.com nameserver = ns1.p14.dynect.net.

wix.com nameserver = ns3.p14.dynect.net.

wix.com nameserver = ns4.p14.dynect.net.

wix.com nameserver = ns2.p14.dynect.net.

From this, we can see that wix.com uses Dyn’s DNS service and because of this, they would have been affected by the DDoS attack on Dyn.

Now let’s have a look at 000webhosts:

$ nslookup -type=ns 000webhost.com

Server: 212.159.6.9

Address: 212.159.6.9#53

Non-authoritative answer:

000webhost.com nameserver = terin.ns.cloudflare.com.

000webhost.com nameserver = emily.ns.cloudflare.com.

Here we can clearly see that 000webhost is using a completely different Name Server provider, which explains why their service stayed up during the DDoS on Dyn – in that they do not use Dyn’s services.

But this does not mean that 000webhost is immune to this kind of attack. In fact, if someone was to perform the same attack on Cloudflare, the only site to be affected in their propaganda image would be themselves.

If you really want to make your service more resilient, you’d need to shell out the extra cash and hire the service of more than one Name Server provider. For example, Pornhub (yeah, I’d never heard of it either 😉 ) uses two providers, one of them being Dyn:

$ nslookup -type=ns pornhub.com

Server: 212.159.6.9

Address: 212.159.6.9#53

Non-authoritative answer:

pornhub.com nameserver = sdns3.ultradns.com.

pornhub.com nameserver = ns2.p44.dynect.net.

pornhub.com nameserver = sdns3.ultradns.net.

pornhub.com nameserver = sdns3.ultradns.org.

pornhub.com nameserver = sdns3.ultradns.biz.

pornhub.com nameserver = ns4.p44.dynect.net.

pornhub.com nameserver = ns1.p44.dynect.net.

pornhub.com nameserver = ns3.p44.dynect.net.

So, whilst Dyn was under attack, users of this particular service were still able to access their business thanks to the service offered by UltraDNS still being available.

Who did it and why?

Sadly no-one knows who did this and why, there are plenty of conspiracy theories out there, but I’m not going to go into that here. What Dyn have confirmed is that the attack came from multiple IP addresses with numbers reaching the thousands. My best guess is that these IP addresses were residential addresses and a compromised Internet of Things (IoT) device was participating in the attack. The growing number of these devices shipping with major security flaws is becoming a big problem with more of these large scale attacks happening recently.

The FBI and Homeland Security are currently investigating the attacks, but I feel if IoT devices were used to execute this attack, they’re going to have a hard time tracking down where the attack was being orchestrated from. So for now, until someone either owns up to the attack, or the US government investigations reveal anything – providing they make it public, we’ll probably never know the true intentions of this attack.

Cheers